Although a

monitum was issued in regard to some of Teilhard's ideas, he has been posthumously praised by

Pope Benedict XVI and other eminent Catholic figures, and his theological teachings were cited by

Pope Francis in the 2015 encyclical,

Laudato si'. The response to his writings by evolutionary biologists has been, with some exceptions, decidedly negative.

Early years[edit]

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born in the Château of Sarcenat,

Orcines commune, some 4 km north-west of

Clermont-Ferrand,

Auvergne,

France, on 1 May 1881, as the fourth of eleven children of librarian Emmanuel Teilhard de Chardin (1844–1932) and of Berthe-Adèle, née de Dompierre d'Hornoys of

Picardy, a great-grandniece of

Voltaire. He inherited the double surname from his father, who was descended on the

Teilhard side from an ancient family of magistrates from

Auvergne originating in

Murat, Cantal, ennobled under

Louis XVIII.

[1]

His father, an amateur

naturalist, collected stones, insects and plants and promoted the observation of nature in the household. Pierre Teilhard's

spirituality was awakened by his mother. When he was 12, he went to the

Jesuit college of Mongré, in

Villefranche-sur-Saône, where he completed

baccalaureates of

philosophy and

mathematics. Then, in 1899, he entered the Jesuit novitiate at

Aix-en-Provence, where he began a philosophical, theological and spiritual career.

When the

Associations Bill of 1901 required congregational associations to submit their properties to state control, some of the Jesuits exiled themselves in the United Kingdom. Young Jesuit students continued their studies in

Jersey. In the meantime, Teilhard earned a licentiate in literature in

Caen in 1902.

Academic career[edit]

From 1905 to 1908, he taught

physics and

chemistry in

Cairo, Egypt, at the

Jesuit College of the Holy Family. He wrote "... it is the dazzling of the East foreseen and drunk greedily ... in its lights, its vegetation, its fauna and its deserts."

[2]

Teilhard studied theology in

Hastings, in

Sussex (United Kingdom), from 1908 to 1912. There he synthesized his scientific, philosophical and theological knowledge in the light of

evolution. At that time he read

L'Évolution Créatrice (The Creative Evolution) by

Henri Bergson, about which he wrote that "the only effect that brilliant book had upon me was to provide fuel at just the right moment, and very briefly, for a fire that was already consuming my heart and mind."

[3] In short, Bergson's ideas helped him to unify his views on matter, life, and energy into a coherent and organic whole.

Paleontology[edit]

Service in World War I[edit]

During the war, he developed his reflections in his diaries and in letters to his cousin, Marguerite Teillard-Chambon, who later published a collection of them.

[6] He later wrote: "...the war was a meeting ... with the Absolute." In 1916, he wrote his first essay:

La Vie Cosmique (

Cosmic life), where his scientific and philosophical thought was revealed just as his mystical life. While on leave from the military he pronounced his solemn vows as a Jesuit in

Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon on 26 May 1918. In August 1919, in

Jersey, he wrote

Puissance spirituelle de la Matière (

The Spiritual Power of Matter).

Research in China[edit]

In 1923 he traveled to China with Father

Emile Licent, who was in charge of a significant laboratory collaboration between the

Natural History Museum in Paris and Marcellin Boule's laboratory in

Tientsin. Licent carried out considerable basic work in connection with missionaries who accumulated observations of a scientific nature in their spare time.

Teilhard wrote several essays, including

La Messe sur le Monde (the

Mass on the World), in the

Ordos Desert. In the following year, he continued lecturing at the Catholic Institute and participated in a cycle of conferences for the students of the Engineers' Schools. Two theological essays on

Original Sin were sent to a theologian at his request on a purely personal basis:

- July 1920: Chute, Rédemption et Géocentrie (Fall, Redemption and Geocentry)

- Spring 1922: Notes sur quelques représentations historiques possibles du Péché originel (Note on Some Possible Historical Representations of Original Sin) (Works, Tome X)

The

Church required him to give up his lecturing at the Catholic Institute in order to continue his geological research in China.

Teilhard traveled again to China in April 1926. He would remain there for about twenty years, with many voyages throughout the world. He settled until 1932 in

Tientsinwith Emile Licent, then in

Beijing. Teilhard made five geological research expeditions in China between 1926 and 1935. They enabled him to establish a general geological map of China. That same year, Teilhard's superiors in the Jesuit Order forbade him to teach any longer.

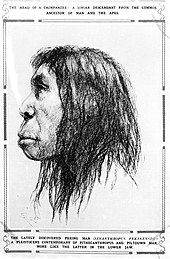

Sketch of "The Lately Discovered Peking Man" published in

The Sphere.

In 1933, Rome ordered him to give up his post in Paris. Teilhard subsequently undertook several explorations in the south of China. He traveled in the valleys of

Yangtze River and

Sichuan in 1934, then, the following year, in

Kwang-If and

Guangdong. The relationship with Marcellin Boule was disrupted; the museum cut its financing on the grounds that Teilhard worked more for the Chinese Geological Service than for the museum.

[citation needed]

During all these years, Teilhard contributed considerably to the constitution of an international network of research in human paleontology related to the whole of eastern and southeastern Asia. He would be particularly associated in this task with two friends, the English/Canadian Davidson Black and the

Scot George Brown Barbour. Often he would visit France or the United States, only to leave these countries for further expeditions.

World travels[edit]

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1947)

In 1937, Teilhard wrote

Le Phénomène spirituel (

The Phenomenon of the Spirit) on board the boat Empress of Japan, where he met the

Raja of

Sarawak. The ship conveyed him to the United States. He received the

Mendel Medal granted by

Villanova University during the Congress of

Philadelphia, in recognition of his works on human paleontology. He made a speech about

evolution, the origins and the destiny of man.

The New York Times dated 19 March 1937 presented Teilhard as the Jesuit who held that

man descended from

monkeys. Some days later, he was to be granted the

Doctor Honoris Causa distinction from

Boston College. Upon arrival in that city, he was told that the award had been cancelled.

[citation needed]

Rome banned his work

L’Énergie Humaine in 1939. By this point Teilhard was based again in France, where he was immobilized by

malaria. During his return voyage to Beijing he wrote

L'Energie spirituelle de la Souffrance (

Spiritual Energy of Suffering) (Complete Works, tome VII).

In 1941, Teilhard submitted to Rome his most important work, Le Phénomène Humain. By 1947, Rome forbade him to write or teach on philosophical subjects. The next year, Teilhard was called to Rome by the Superior General of the Jesuits who hoped to acquire permission from the Holy See for the publication of Le Phénomène Humain. However, the prohibition to publish it that was previously issued in 1944 was again renewed. Teilhard was also forbidden to take a teaching post in the Collège de France. Another setback came in 1949, when permission to publish Le Groupe Zoologique was refused.

Teilhard was nominated to the

French Academy of Sciences in 1950. He was forbidden by his Superiors to attend the International Congress of Paleontology in 1955. The Supreme Authority of the Holy Office, in a decree dated 15 November 1957, forbade the works of de Chardin to be retained in libraries, including those of

religious institutes. His books were not to be sold in Catholic bookshops and were not to be translated into other languages.

Further resistance to Teilhard's work arose elsewhere. In April 1958, all Jesuit publications in Spain ("Razón y Fe", "Sal Terrae","Estudios de Deusto", etc.) carried a notice from the Spanish Provincial of the Jesuits that Teilhard's works had been published in Spanish without previous ecclesiastical examination and in defiance of the decrees of the Holy See. A decree of the Holy Office dated 30 June 1962, under the authority of Pope John XXIII, warned that "... it is obvious that in philosophical and theological matters, the said works [Teilhard's] are replete with ambiguities or rather with serious errors which offend Catholic doctrine. That is why... the Rev. Fathers of the Holy Office urge all Ordinaries, Superiors, and Rectors... to effectively protect, especially the minds of the young, against the dangers of the works of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin and his followers" (AAS, 6 August 1962).

The

Diocese of Rome on 30 September 1963 required Catholic booksellers in Rome to withdraw his works as well as those that supported his views.

[9]

Grave at the cemetery of the former Jesuit novitiate in Hyde Park, New York

Teilhard died in New York City, where he was in residence at the Jesuit

Church of St. Ignatius Loyola,

Park Avenue. On 15 March 1955, at the house of his diplomat cousin Jean de Lagarde, Teilhard told friends he hoped he would die on

Easter Sunday.

[10] On the evening of Easter Sunday, 10 April 1955, during an animated discussion at the apartment of Rhoda de Terra, his personal assistant since 1949, Teilhard suffered a heart attack and died.

[10] He was buried in the cemetery for the New York Province of the Jesuits at the Jesuit novitiate,

St. Andrew-on-Hudson, in

Hyde Park, New York. With the moving of the novitiate, the property was sold to the

Culinary Institute of America in 1970.

Teachings[edit]

His posthumously published book,

The Phenomenon of Man, set forth a sweeping account of the unfolding of the

cosmos and the evolution of matter to humanity, to ultimately a reunion with Christ. In the book, Teilhard abandoned literal interpretations of creation in the

Book of Genesis in favor of allegorical and theological interpretations. The unfolding of the material

cosmos is described from

primordial particles to the development of life, human beings and the

noosphere, and finally to his vision of the

Omega Point in the future, which is "pulling" all creation towards it. He was a leading proponent of

orthogenesis, the idea that

evolution occurs in a directional, goal-driven way. Teilhard argued in

Darwinian terms with respect to biology, and supported the

synthetic model of evolution, but argued in

Lamarckian termsfor the development of culture, primarily through the vehicle of education.

[12] Teilhard made a total commitment to the evolutionary process in the 1920s as the core of his spirituality, at a time when other religious thinkers felt evolutionary thinking challenged the structure of conventional Christian faith. He committed himself to what the evidence showed.

[13]

Teilhard made sense of the

universe by assuming it had a

vitalist evolutionary process.

[14][15] He interprets complexity as the axis of evolution of matter into a geosphere, a biosphere, into consciousness (in man), and then to supreme consciousness (the Omega Point).

Teilhard's unique relationship to both

paleontology and

Catholicism allowed him to develop a highly progressive,

cosmic theology which takes into account his evolutionary studies. Teilhard recognized the importance of bringing the Church into the modern world, and approached

evolution as a way of providing ontological meaning for Christianity, particularly creation theology. For Teilhard, evolution was "the natural landscape where the history of salvation is situated."

[16]

Teilhard's cosmic theology is largely predicated on his interpretation of

Pauline scripture, particularly Colossians 1:15-17 (especially verse 1:17b) and 1 Corinthians 15:28. He drew on the Christocentrism of these two Pauline passages to construct a cosmic theology which recognizes the absolute primacy of Christ. He understood creation to be "a

teleological process towards union with the Godhead, effected through the incarnation and redemption of Christ, 'in whom all things hold together' (Col. 1:17)."

[17] He further posited that creation would not be complete until each "participated being is totally united with God through Christ in the

Pleroma, when God will be 'all in all' (1Cor. 15:28)."

[17]

Teilhard's life work was predicated on his conviction that human spiritual development is moved by the same universal laws as material development. He wrote, "...everything is the sum of the past" and "...nothing is comprehensible except through its history. 'Nature' is the equivalent of 'becoming', self-creation: this is the view to which experience irresistibly leads us. ... There is nothing, not even the human soul, the highest spiritual manifestation we know of, that does not come within this universal law."

[18] The Phenomenon of Man represents Teilhard's attempt at reconciling his religious

faith with his academic interests as a

paleontologist.

[19] One particularly poignant observation in Teilhard's book entails the notion that

evolution is becoming an increasingly optional

process.

[19] Teilhard points to the societal problems of

isolation and

marginalization as huge

inhibitors of evolution, especially since evolution requires a unification of

consciousness. He states that "no evolutionary future awaits anyone except in association with everyone else."

[19] Teilhard argued that the human condition necessarily leads to the psychic unity of humankind, though he stressed that this unity can only be voluntary; this voluntary psychic unity he termed "unanimization." Teilhard also states that "evolution is an ascent toward consciousness", giving

encephalization as an example of early stages, and therefore, signifies a continuous upsurge toward the

Omega Point[19] which, for all intents and purposes, is

God.

Teilhard also used his perceived correlation between spiritual and material to describe Christ, arguing that Christ not only has a

mystical dimension but also takes on a physical dimension as he becomes the organizing principle of the universe—that is, the one who "holds together" the universe (Col. 1:17b). For Teilhard, Christ forms not only the

eschatological end toward which his mystical/ecclesial body is oriented, but he also "operates physically in order to regulate all things"

[20] becoming "the one from whom all creation receives its stability."

[21] In other words, as the one who holds all things together, "Christ exercises a supremacy over the universe which is physical, not simply juridical. He is the unifying center of the universe and its goal. The function of holding all things together indicates that Christ is not only man and God; he also possesses a third aspect—indeed, a third nature—which is cosmic."

[22] In this way, the Pauline description of the

Body of Christ is not simply a mystical or

ecclesial concept for Teilhard; it is

cosmic. This cosmic Body of Christ "extend[s] throughout the universe and compris[es] all things that attain their fulfillment in Christ [so that] ... the Body of Christ is the one single thing that is being made in creation."

[23] Teilhard describes this cosmic amassing of Christ as "Christogenesis." According to Teilhard, the universe is engaged in Christogenesis as it evolves toward its full realization at

Omega, a point which coincides with the fully realized Christ.

[17] It is at this point that God will be "all in all" (1Cor. 15:28c).

Our century is probably more religious than any other. How could it fail to be, with such problems to be solved? The only trouble is that it has not yet found a God it can adore.

[19]

Relationship with the Catholic Church[edit]

In 1925, Teilhard was ordered by the

Jesuit Superior General Wlodimir Ledóchowski to leave his teaching position in France and to sign a statement withdrawing his controversial statements regarding the doctrine of

original sin. Rather than leave the Society of Jesus, Teilhard signed the statement and left for China.

This was the first of a series of condemnations by certain

ecclesiastical officials that would continue until after Teilhard's death. The climax of these condemnations was a 1962

monitum (warning) of the

Holy Office cautioning on Teilhard's works. It said:

[24]

Several works of Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, some of which were posthumously published, are being edited and are gaining a good deal of success. Prescinding from a judgement about those points that concern the positive sciences, it is sufficiently clear that the above-mentioned works abound in such ambiguities and indeed even serious errors, as to offend Catholic doctrine. For this reason, the most eminent and most revered Fathers of the Holy Office exhort all Ordinaries as well as the superiors of Religious institutes, rectors of seminaries and presidents of universities, effectively to protect the minds, particularly of the youth, against the dangers presented by the works of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin and of his followers.

The Holy Office did not place any of Teilhard's writings on the

Index Librorum Prohibitorum (Index of Forbidden Books), which existed during Teilhard's lifetime and at the time of the 1962 decree.

Shortly thereafter, prominent clerics mounted a strong theological defense of Teilhard's works.

Henri de Lubac (later a Cardinal) wrote three comprehensive books on the theology of Teilhard de Chardin in the 1960s.

[25] While de Lubac mentioned that Teilhard was less than precise in some of his concepts, he affirmed the orthodoxy of Teilhard de Chardin and responded to Teilhard's critics: "We need not concern ourselves with a number of detractors of Teilhard, in whom emotion has blunted intelligence".

[26] Later that decade

Joseph Ratzinger, a German theologian who became Pope Benedict XVI, spoke glowingly of Teilhard's Christology in Ratzinger's

Introduction to Christianity:

[27]

It must be regarded as an important service of Teilhard de Chardin's that he rethought these ideas from the angle of the modern view of the world and, in spite of a not entirely unobjectionable tendency toward the biological approach, nevertheless on the whole grasped them correctly and in any case made them accessible once again. Let us listen to his own words: The human monad "can only be absolutely itself by ceasing to be alone". In the background is the idea that in the cosmos, alongside the two orders or classes of the infinitely small and the infinitely big, there is a third order, which determines the real drift of evolution, namely, the order of the infinitely complex. It is the real goal of the ascending process of growth or becoming; it reaches a first peak in the genesis of living things and then continues to advance to those highly complex creations that give the cosmos a new center: "Imperceptible and accidental as the position they hold may be in the history of the heavenly bodies, in the last analysis the planets are nothing less than the vital points of the universe. It is through them that the axis now runs, on them is henceforth concentrated the main effort of an evolution aiming principally at the production of large molecules." The examination of the world by the dynamic criterion of complexity thus signifies "a complete inversion of values. A reversal of the perspective".

This leads to a further passage in Teilhard de Chardin that is worth quoting in order to give at least some indication here, by means of a few fragmentary excerpts, of his general outlook. "The Universal Energy must be a Thinking Energy if it is not to be less highly evolved than the ends animated by its action. And consequently ... the attributes of cosmic value with which it is surrounded in our modern eyes do not affect in the slightest the necessity obliging us to recognize in it a transcendent form of Personality."

What our contemporaries will undoubtedly remember, beyond the difficulties of conception and deficiencies of expression in this audacious attempt to reach a synthesis, is the testimony of the coherent life of a man possessed by Christ in the depths of his soul. He was concerned with honoring both faith and reason, and anticipated the response to John Paul II's appeal: "Be not afraid, open, open wide to Christ the doors of the immense domains of culture, civilization, and progress".

[28]

In his own poetic style, the French Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin liked to meditate on the Eucharist as the first fruits of the new creation. In an essay called The Monstrance he describes how, kneeling in prayer, he had a sensation that the Host was beginning to grow until at last, through its mysterious expansion, "the whole world had become incandescent, had itself become like a single giant Host". Although it would probably be incorrect to imagine that the universe will eventually be transubstantiated, Teilhard correctly identified the connection between the Eucharist and the final glorification of the cosmos.

Hardly anyone else has tried to bring together the knowledge of Christ and the idea of evolution as the scientist (paleontologist) and theologian Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., has done. ... His fascinating vision ... has represented a great hope, the hope that faith in Christ and a scientific approach to the world can be brought together. ... These brief references to Teilhard cannot do justice to his efforts. The fascination which Teilhard de Chardin exercised for an entire generation stemmed from his radical manner of looking at science and Christian faith together.

Pope Benedict XVI in his book

Spirit of the Liturgy incorporates Teilhard's vision as a touchstone of the Catholic Mass:

[31]

And so we can now say that the goal of worship and the goal of creation as a whole are one and the same—divinization, a world of freedom and love. But this means that the historical makes its appearance in the cosmic. The cosmos is not a kind of closed building, a stationary container in which history may by chance take place. It is itself movement, from its one beginning to its one end. In a sense, creation is history. Against the background of the modern evolutionary world view, Teilhard de Chardin depicted the cosmos as a process of ascent, a series of unions. From very simple beginnings the path leads to ever greater and more complex unities, in which multiplicity is not abolished but merged into a growing synthesis, leading to the "Noosphere" in which spirit and its understanding embrace the whole and are blended into a kind of living organism. Invoking the epistles to the Ephesians and Colossians, Teilhard looks on Christ as the energy that strives toward the Noosphere and finally incorporates everything in its "fullness". From here Teilhard went on to give a new meaning to Christian worship: the transubstantiated Host is the anticipation of the transformation and divinization of matter in the christological "fullness". In his view, the Eucharist provides the movement of the cosmos with its direction; it anticipates its goal and at the same time urges it on.

in July 2009, Vatican spokesman

Federico Lombardi said, "By now, no one would dream of saying that [Teilhard] is a heterodox author who shouldn't be studied."

[32]

The philosopher

Dietrich von Hildebrand criticized severely the work of Teilhard. According to this philosopher, in a conversation after a lecture by Teilhard: "He (Teilhard) ignored completely the decisive difference between nature and supernature. After a lively discussion in which I ventured a criticism of his ideas, I had an opportunity to speak to Teilhard privately. When our talk touched on

St. Augustine, he exclaimed violently: 'Don’t mention that unfortunate man; he spoiled everything by introducing the supernatural.'"

[34] Von Hildebrand writes that Teilhardism is incompatible with Christianity, substitutes efficiency for sanctity, dehumanizes man, and describes love as merely cosmic energy.

Evaluations by scientists[edit]

According to

Daniel Dennett (2014), "it has become clear to the point of unanimity among scientists that Teilhard offered nothing serious in the way of an alternative to orthodoxy; the ideas that were peculiarly his were confused, and the rest was just bombastic redescription of orthodoxy."

[35] Steven Rose wrote

[year needed] that "Teilhard is revered as a mystic of genius by some, but amongst most biologists is seen as little more than a

charlatan."

[36]

In 1961, British immunologist and Nobel laureate

Peter Medawar wrote a scornful review of

The Phenomenon Of Man for the journal

Mind:

[37] "the greater part of it, I shall show, is nonsense, tricked out with a variety of metaphysical conceits, and its author can be excused of dishonesty only on the grounds that before deceiving others he has taken great pains to deceive himself"; "In spite of all the obstacles that Teilhard perhaps wisely puts in our way, it is possible to discern a train of thought in

The Phenomenon of Man". Evolutionary biologist

Richard Dawkins called Medawar's review "devastating" and

The Phenomenon of Man "the quintessence of bad poetic science".

[38]

Sir Julian Huxley, the evolutionary biologist, in the preface to the 1955 edition of

The Phenomenon of Man, praised the thought of Teilhard de Chardin for looking at the way in which human development needs to be examined within a larger integrated universal sense of evolution, though admitting he could not follow Teilhard all the way.

[39] Theodosius Dobzhansky, writing in 1973, drew upon Teilhard's insistence that evolutionary theory provides the core of how man understands his relationship to nature, calling him "one of the great thinkers of our age".

[40] David Sloan Wilson, an evolutionary biologist, in a 2012 interview judged that Teilhard remains "amazingly relevan[t]" even though he has been "largely forgotten as a scientist", and that he had anticipated his own work in

multilevel selection theory.

[41]

George Gaylord Simpson felt that if Teilhard were right, the lifework "of Huxley, Dobzhansky, and hundreds of others was not only wrong, but meaningless", and was mystified by their public support for him.

[42] He considered Teilhard a friend and his work in paleontology extensive and important, but expressed strongly adverse views of his contributions as scientific theorist and philosopher.

[43]

Brian Swimme wrote "Teilhard was one of the first scientists to realize that the human and the universe are inseparable. The only universe we know about is a universe that brought forth the human."

[44]

Teilhard's work also inspired philosophical ruminations by Italian laureate architect

Paolo Soleri, artworks such as French painter

Alfred Manessier's

L'Offrande de la terre ou Hommage à Teilhard de Chardin and American sculptor

Frederick Hart's

acrylic sculpture

The Divine Milieu: Homage to Teilhard de Chardin.

[53] A sculpture of the Omega Point by Henry Setter, with a quote from Teilhard de Chardin, can be found at the entrance to the Roesch Library at the

University of Dayton.

[54] The Spanish painter

Salvador Dali was fascinated by Teilhard de Chardin and the Omega Point theory. His 1959 painting

The Ecumenical Council (painting) is said to represent the "interconnectedness" of the Omega Point.

[55]

Edmund Rubbra's 1968 Symphony No. 8 is titled

Hommage à Teilhard de Chardin.

The Embracing Universe an oratorio for choir and 7 instruments composed by Justin Grounds to a libretto by Fred LaHaye saw its first performance in 2019. It is based on the life and thought of Teilhard de Chardin.

[56]

The De Chardin Project, a play celebrating Teilhard's life, ran from 20 November to 14 December 2014 in Toronto, Canada.

[57] The Evolution of Teilhard de Chardin, a documentary film on Teilhard's life, was scheduled for released in 2015.

[57]

Founded in 1978, George Addair based much of Omega Vector on Teilhard's work.

The American physicist

Frank J. Tipler has further developed Teilhard's

Omega Point concept in two controversial books,

The Physics of Immortality and the more theologically based Physics of Christianity.

[58] While keeping the central premise of Teilhard's Omega Point (i.e. a universe evolving towards a maximum state of complexity and consciousness) Tipler has supplanted some of the more mystical/ theological elements of the OPT with his own scientific and mathematical observations (as well as some elements borrowed from Freeman

Dyson's eternal intelligence theory).

[59][60]

In 1972, the Uruguayan priest Juan Luis Segundo, in his five-volume series

A Theology for Artisans of a New Humanity, wrote that Teilhard "noticed the profound analogies existing between the conceptual elements used by the natural sciences — all of them being based on the hypothesis of a general evolution of the universe."

[61]

Influence on the New Age movement[edit]

Teilhard has had a profound influence on the

New Age movement and has been described as "perhaps the man most responsible for the spiritualization of evolution in a global and cosmic context".

[62]

Teilhard’s quote on likening the discovery of the power of love to the second time man will have discovered the power of fire was quoted in the sermon of the Most Reverend Michael Curry, Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church, during the

wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle on 20 May 2018.

[63]

Bibliography

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου